On June 20, 2024, I attended the annual Ontario Bar Association’s Elder Law Day, where several informative presentations noted the rise in personal care disputes. Speakers also explored approaches that lawyers might consider to manage these disputes. The presentations triggered me to write about common issues we see related to the Power of Attorneys for Care. I also offer considerations to help lawyers and advisors deal with personal care disputes.

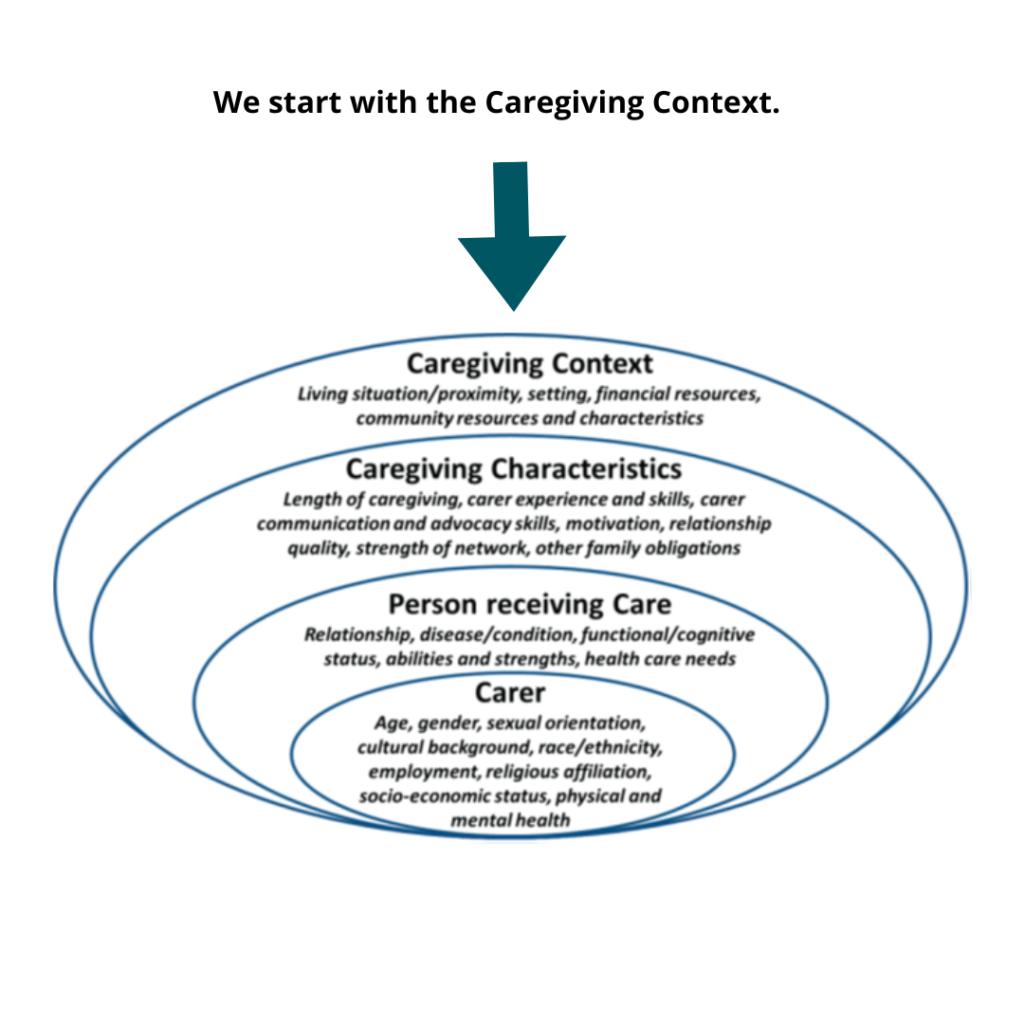

This article is the third in a comprehensive series about resolving care disputes. The first article emphasized the necessity of evaluating the caregiving situation before embarking on conflict resolution. We proposed this model, with four concentric layers, to guide the initial detailed assessment of the caregiving situation.

- Caregiving context

- Caregiving characteristics

- Person receiving care

- Carer

For a detailed exploration of common sibling disputes, I invite you to refer to my article, Navigating Elder Management: Common Sibling and Stepsibling Disputes.

As part of the contextual assessment, it is important to identify the decision-makers and the influencers of those decisions. In cases where a person is deemed incapable of making some or all personal care decisions, the Attorney for Personal Care assumes the role of the substitute decision-maker. To effectively carry out this role, the attorney must have a comprehensive understanding of their roles and responsibilities as outlined in the Substitute Decisions Act, 1992 and the Health Care Consent Act, 1996.

Why do so many disputes arise in this area? Here are some common reasons.

Issues that arise when the role of Attorney for Personal Care is assumed.

- POA documents are not standardized to include common language and applicable content.

a. Many documents talk about “medical decision-making” but do not clarify specifics about a person’s wishes or instructions. For example, at the end of life, does the person wish to have critical care and life support, and under what circumstances?

b. POA for Personal Care documents do not include the other elements of personal care, such as shelter, hygiene, safety, clothing, and nutrition. Some attorneys believe that they only act on critical medical decisions, such as choosing to end life support, and are surprised to learn about decisions required for the other elements of personal care. - POAs are unaware they have been appointed until a healthcare crisis occurs. Therefore, they may have no understanding of the grantor’s wishes yet must act in a crisis. In these circumstances and depending on the care situation, the attorney may also resent the burden placed upon them with this role, especially if it has been going on for years.

- POAs may have a vague idea of the grantor’s wishes for care, but no written plan was carefully considered when the grantor was capable. For example, where do you wish to live if you require assistance and lose the capacity to make your own care decisions? How would you like to be cared for? By whom?

Common Issues Between Attorneys for Personal Care and Family Members

- The costs of care required are often a flashpoint for disputes. Usually, there is little or no discussion about the costs or funds set aside to care for the individual. If there is a different POA for Property, then the potential for cost disagreements can easily escalate.

- The attorney tries to restrict visitation and communication with the incapable parent or loved one, believing that they can control all access.

- The attorney makes decisions unilaterally without consulting the incapable person to the extent they can be consulted and without consulting supportive family members. For example, the POA brother with six siblings only consults with a brother who usually defers to him about his mother’s care and refuses to consult with the other four siblings even though they visit their mother regularly.

Considerations to Prevent POA for Personal Care Disputes

Care disputes are often the most complex and nasty disputes on record. Ultimately, these disputes usually boil down to “control” over a parent or eventual control of finances. Family relationships are often fractured forever. So, what considerations may defuse these disputes before they really get underway?

- Educate clients on the roles and responsibilities of a POA for Personal Care. It would be helpful to have a pamphlet written in layperson’s terms that clearly and succinctly outlines an attorney’s roles, responsibilities, and obligations.

- When drafting a POA for Personal Care, it would be helpful to see more specific content regarding decisions, wishes, and instructions, not only for medical and healthcare decision-making but also for other elements of care.

- For public education and client information, a clear and comprehensive guide to the Substitute Decisions Act would benefit clients and their families. PBP Law in Toronto has a comprehensive guide available on its website.

- Recommend to clients that they seek advice on creating a comprehensive life plan while they are capable of thinking through their wishes and can consider such things as where they would like to live, what type of care they would prefer, what level of services they wish to see, etc. Working with their advisors, the plan could be costed out for current and future care, and then financial strategies discussed on how to pay for it. For example, estate lawyers might recommend using a joint spousal trust to pay for care costs during their lifetime.

- As part of the planning process, facilitate a conversation between the grantor and the substitute decision-maker so there is a discussion about wishes and instructions. Ideally, a family meeting, including the grantor and the Attorney for Personal Care, could follow, where family members would understand the grantor’s wishes and discuss how they could work together to fulfil them.

When an elderly parent or loved one becomes incapable of making care decisions, the care context will change dramatically. Families and advisors will need to reassess the situation and determine how they will work with the substitute decision-maker to fulfil the parent’s wishes.

Preparing people for the role of Attorney for Personal Care is critical to reducing the exponential rise in care disputes.

0 Comments